IN A DEADLY way, waiting for battle to begin was flirtation. A tease.

When would the Germans strike? The week saw a flurry of fighting on the Western Front, some of it intense. The distinction between this and an all-out offensive may not have been apparent to troops unlucky enough to be at the receiving end — but commanders were not fooled.

Yet, even these feints did damage aplenty. Following a spell of dry weather, the Yser front was no longer the waterlogged quagmire of recent times. That was great if you wanted to avoid drowning in mud, but the downside was that shells exploded more reliably and more dangerously. On 5th March, the Germans launched a heavy bombardment — shells and poison gas falling all over the place — and then followed it up with an assault by their storm troopers. The brunt of this was borne between Nieuport on the coast and Pervyse, home of the British volunteers, the so-called”‘Madonnas”, Mairi Chisholm and Elsie Knocker. But the scale was too small to be really alarming: the Belgians retook the line plus 100 prisoners and seven machine-guns.

The Madonnas of Pervyse

The British faced raids too, mainly around Ypres and Armentieres. These too were seen off, albeit at a cost. Allied fatalities that week were recorded as 2,235 — a number which did nothing to comfort Haig, who also received news on 10th March that there were now 185 German divisions on the Western Front. It was a discomfiting total for a commander already deeply concerned at his shortage of manpower.

Intelligence at GHQ believed that the brunt of German attack was likely to fall on the Third and Fifth Armies. The Fifth Army was a problem in its own right — two problems in fact. One was that, with 40 miles of front to protect and a woefully inadequate labour force of just 8,830, it was grotesquely undermanned. The other problem was General Gough.

On 5th March, Derby, Minister of War, wrote to Haig:

It looks now as if an attack might come within a very short time on your front, and on that part of the front of which Gough is in command. You know my feelings with regard to that particular officer.

While personally I naturally have no knowledge of his fighting capacity, still, it has been borne upon me from all sides, civil and military, that he does not have the confidence of the troops he commands…

I know that on you must be the responsibility, and you must decide on his retention or not, but if by any chance you yourself have any doubts on the subject, I hope by this indefinite offer… to give you a loophole which would make your task easier if you desired to make a change…

Haig wanted to stick with Gough, arguing:

The French handed over to him a wide front with no defences, and Gough has not enough labour for the work.

Anyway, to remove a commander on the eve of a great battle was hardly a morale-builder.

Sir Hubert Gough

Haig had long disciplined himself to work within the parameters decided by the men who ran the country. But serving a Prime Minister who had no intention of releasing able-bodied men from Britain added greatly to the dangers of the present situation.

The consequences of Lloyd George’s obduracy were felt everywhere. On 5th March, Lieutenant Colonel Feilding wrote to his wife from Tincourt:

We were unexpectedly relieved and marched back last night to this village…

The battalion wants a rest. It had been up for forty-two days when, last night, it was relieved, and even now I doubt if the rest is in sight, since an order has just come in to go up tomorrow for the day, to dig. I leave you to imagine the state of the men’s bodies and clothing after so long a time in the line, almost without a wash.

There were those, especially in Britain and France, who were sometimes heard to mutter why it was that the Americans were not more fully engaged in the fighting — why it was that, having been slow to commit to the war in the first place, they seemed equally slow at putting their backs into it.

It feels curious that, while Haig was presently scrabbling round for any able-bodied man he could find, Pershing was — still — undertaking what seemed like a Grand Tour. In reality, this was an exhausting schedule which involved visiting American bases and personnel, and forging relationships with the French. His diary for 8th March records that, after a long day, on a bad road, returning to Paris, his group stopped “at a little country hotel where we had an excellent dinner, ‘vin compris’ which, with a liberal pourboire, cost us five francs 50 apiece”.

General John Pershing

Haig’s preoccupations were more battle-based. Even so, some delay between America’s entry into the war and her practical impact was to be expected. Her forces had 3,000 miles of Atlantic ocean to traverse before arriving at the scene of battle, for one thing.

Given the relative inexperience of the Americans, however, the complacency with which one or two approached the prospect of fighting might strike an impartial observer as a little out of place. The American surgeon, Dr Harvey Cushing, on his way back to France from England on 7th March, winced inwardly at behaviour he witnessed:

Two spick and span West Pointers —-a colonel and a major — just out of a bandbox — tight-fitting, neatly pressed thin uniforms, paper-soled pointed riding boots — also very complaining. Such a contrast to the civilian officers of the B.E.F. just returning from leave with all emotions buried behind The Times after a ‘So long, old girl’, and ‘Bring back a D.S.O., Charlie’, on the platform. Charlie, like most of the others, in heavy trench boots and enveloped in a soiled raincoat over a ragged ‘British warm’ — many of them with wound stripes and the spectral Mons-Star ribbon in addition to others, indicating long as well as meritorious service.

‘Rotten town London — had to wait fifteen minutes for our hotel bill — almost missed breakfast and the train — never want to see the d…..d place again’. ‘Training our men to shoot; British have been all fired stupid; when we break through there’ll be open warfare and the men’ll know what to do; lots of… great fighters, fine shots. Now if you’d only done this at Cambrai etc. etc.’

The patient young captain to whom this was chiefly addressed showed wonderful restraint.

‘You see, we’re fed up with the war. That’s the way we used to feel; but then we’ve made so many mistakes, and your country understands administration so much better and has no red tape, and will show us the way, I’m sure.’

‘We certainly will, we’ve got 600,000 over here already, and they’re coming at the rate of 200,000 a month, all arrangements made for it — isn’t that going some?’

And so it went on all the way to Folkestone. I saw them later shivering on the packet’s deck —-no one taking any notice of them. They have much to learn and they’re probably at bottom very brave and capable, though tactless, fellows.

One reason, perhaps, for the jaundiced view of London may have been the recent air raids to which the city had been subjected. As the weather improved so aerial activity increased. There was no moon, but airmen on both sides had refined their combat skills radically over recent months. On 6th March, two Gothas — that was out of seven or eight which had set out — penetrated Britain’s aerial defences and bombed London and the Home Counties: 23 people were killed and 39 injured.

The Germans also bombed Paris: a major raid on the city overnight on 8th March saw 13 people killed and 50 injured. When they returned three nights later, civil defence succeeded in bringing down four enemy aircraft, but could do nothing about a stampede of panic-filled civilians trying to escape the bombs by heading into the bowels of the Bolivar metro station. The immediate problem had been a pair of doors which only opened outward and, in the crush which ensued, some 76 people were killed.

Bomb crater in Paris, 1918

For their part, the British carried out daylight raids on Mainz and Stuttgart, outings which sound tame by comparison, although enemy propaganda made efforts to use them to rouse national indignation. In fact, most of what we might now call the German PR machine was bent on trying to foment a mood of national rejoicing. Russia had capitulated the previous week at Brest-Litovsk and it made sense for the German people to hang out the bunting.

There was little chance of that, however. The different factions — Whites, Reds, Ukrainian nationals and so forth — were ever more fissiparous, which was enough to ensure that fighting in the East continued for the moment. The Germans were also determined to ensure that they held on to any gains the Russians had just signed away. By 10th March, they were approaching the port of Odessa.

Princess Blucher, in Berlin, looked on these developments without enthusiasm:

The Russian Peace, although greeted with a great show of flags and ringing of bells and universal holidays for the school-children, has on the whole been received with shakes of the head and disbelief in the duration of such a treaty. Fighting still continues between the German troops and the Red Guards, and one hears horrible stories of bloodshed and anarchy. Not only are German officers and soldiers being murdered in their beds and their houses set on fire over their heads, but many great Russian magnates are being treated in the same way.

German street scene, 1918

The Germans here are all boasting of the future happy state of the country when it has come to know the blessings of Prussian law and order, whilst the Annexationists and Imperialists are pluming their feathers in great style, under the pretext of re-establishing public order. A German armed force now occupies territories whose populations are pre-eminently Russian, and the Commercial Treaty of 1904 has been renewed in favour of the German agrarians.

To the victor, the spoils. In this case, however, Germany was not destined to enjoy them for long.

The hubris of the German authorities at this moment fortified existing prejudice. The mother of Chaplain Julian Bickersteth wrote in her diary on 5th March:

The Germans are treating the Russians and poor Romanians abominably…

She had a point about the Romanians. It is hard to deny that Queen Marie, even at the best of times, was inclined towards histrionics, but the vengeful peace treaty extracted by the Germans propelled her now into grand opera. On 8th March:

I threw myself into a corner of Lisabetta’s large sofa and asked Enescu to play us Lequeux’s symphony. And there, surrounded by the friends who tomorrow are to leave us to our humiliation and despair, I listened with all my soul to that superhumanly exquisite music, and in its very notes I seemed to hear the agony of our dying country.

Queen Marie: Patriot and Diva

Mrs Bickersteth, a more feet-on-the-ground type, had similarly harsh words about Germany’s ally, Turkey:

The Turks meanwhile are massacring all the remaining Armenians they can find in Asia Minor, putting to the sword ‘all men, boys and male infants’. The world seems given over to the devil at the moment.

While these horrors unfolded, the British were advancing slowly but surely in Palestine, crossing the Wadi Auja in the Jordan valley on 9th March and capturing the height of Tel Asur, north of Jerusalem. Their modest success here was eagerly lapped up by a public which had come, increasingly, to doubt the likelihood of early victories in France and Belgium.

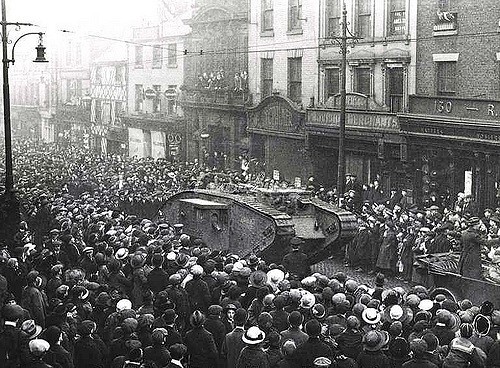

Yet the public mood of realism — even, at times, of scepticism — did not seem to reduce Britain’s determination to see the conflict through, right to the end. Public opinion still inveighed against conchies, and all tiers of society continued to raise money. The new fund-raising wheeze was organised around tanks, which were sent on tour throughout 1918 in an effort to urge people to loan their savings to the government as war bonds.

In a way which may baffle readers a century later, the public found the sight of tanks extraordinarily exciting: they were the last word in technology, after all, and their prominence in the recent battle of Cambrai endowed them with special glamour. Six arrived in London for Tank Week commencing on 4th March: Nelson was stationed near the Royal Exchange; Julian, Old Bill, Drake and Iron Rations were dubbed “Wandering Tanks” and a veteran of Cambrai, Egbert, was displayed in Trafalgar Square.

Phrynette, The Sketch magazine’s gossip columnist, commented:

I paid an early morning call on ‘Egbert of Cambrai’ now in Trafalgar Square, somewhat battered, four men having been killed in him recently. Two charming, fur-clad ladies were sitting on ammunition cases inside, very busy stamping certificates, and a brace of sentries guarded his hull carefully. There was a tremendous crowd in the Square and hawkers were doing a brisk business…

Egbert and crowd (starved of other choices of entertainment?)

You were allowed — the greatest thrill imaginable — to look inside the tank — but only after purchasing war bonds. Commercial interests got in on the act, of course: the band of the Coldstream Guards was requisitioned by Drapkin’s, the cigarette company, to provide cheering music and generally to contribute to a carnival atmosphere.

Quite apart from the pleasures of eyeing the latest military hardware, the occasion also lent itself to eyeing up members of the upper classes. Society ladies volunteered to administer the war bonds process and it was reported that one woman “bought seven War Bonds she could ill afford in order to have a close look at Lady Swaythling’s pretty frock”. In an effort to loosen purse strings, relics of battles past were temptingly displayed: there was a mobile pigeon-cote from which Queen Alexandra bought her war certificates, while Lady Drogheda distributed leaflets from the gondola of a captured Zeppelin.

The sums raised were not merely impressive — they were staggering. The Daily Telegraph purred approvingly on the great “patriotic response” when over £4.5 million was raised on the first day. The figure was more than doubled on the second day. By week’s end, taking into account other fundraising enterprises, Londoners had stumped up to the tune of £112 million — around £6 billion in today’s money.

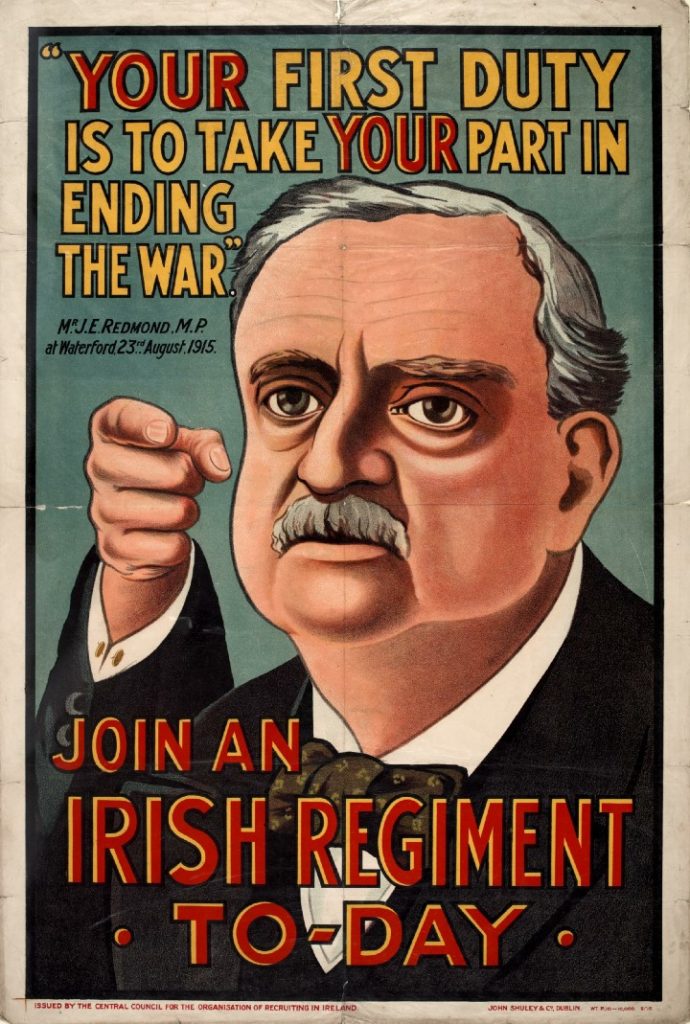

One person who would not live to see the spectacle was John Redmond, long-serving leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. He died of heart failure in London on 6th March at the age of 61, and there is a particular poignance to the passing of this voice of reasonableness at a moment when the world at large, and Ireland in particular, seemed to have abandoned faith in moderation. On his deathbed, he told his priest, “I am a broken-hearted man.”

It is not hard to see why: Redmond was one of the architects of the Home Rule settlement, the introduction of which had been delayed for the duration of the war. He had urged Irishmen to volunteer, moved by the simple logic that loyalty would glean gratitude:

Let Irishmen come together in the trenches,

he had said,

and risk their lives together and spill their lives together, and I say there is no power on earth that, when they come home, can induce them to turn as enemies upon one another.

Yet his reward had been the brutal suppression of the Easter Rising of 1916 and, by the time of his death, Redmond’s party was marginalised by Sinn Fein, an altogether tougher nut. Redmond, shouldering these disappointments in his final years, may have regretted living more than he dreaded death.

Being weary of life — weary of the life they were leading, at least — was something understood by many soldiers of all armies. Siegfried Sassoon, now in Egypt with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers at Base Camp, gives a hint of this in his diary:

Along the main road that runs through the camp parties of Turkish prisoners march, straggling and hopeless, slaves of war, guarded by a few British soldiers with fixed bayonets. These prisoners are killing time. One of them was shot last week, for striking an officer. A moment of anger, then probably fear, and a swift death. He has escaped.

The idea that death was an escape from the travails of life — and of war, especially — had great potency. One thinks not merely of soldiers, but also those at sea. Sailors lived, minute by minute, in the knowledge that they were never more than a well-aimed torpedo away from a freezing and lonely death. The randomness of fate added to the burden of loneliness they each carried.

Even so, fortune could sometimes smile. On 10th March, there was another German attack on a hospital ship — this time, HS Guildford Castle. She was proceeding through the Bristol Channel, flying the Red Cross flag and with all her navigation lights on, but this was not enough to dissuade a submarine from firing two torpedoes at her. One missed, and the other failed to explode. There were 438 wounded soldiers aboard at the time, as well as the crew and medical staff and, thanks to the vagaries of technology, a major disaster was averted.

The Germans did not enjoy a monopoly on dastardly behaviour — but, in the matter of hospital ships, a recklessness seems to have overtaken them. It is not difficult to see how they rationalised this: they believed the British were starving their civilians, and in the wake of that, all non-combatants were fair game.

In a letter home this week, Burgon Bickersteth recalled a conversation with his Colonel behind the lines which offers a very authentic take on popular attitudes towards the enemy:

[The Colonel told me] ‘I intend to teach my children to hate the Germans, and to teach them to teach their children to hate the Germans’.

What is one to say or think? Faced on all sides with the handiwork of the Huns, damage some of it necessary from the military point of view, much of it merely spiteful, it is difficult to take any sane view.

For sanity, one turns — as always — to Rowland Feilding. He reported to his wife on 6th March that he had, by chance, stumbled across his 19-year-old nephew, Osmund Stapleton-Bretherton, of the 9th Lancers:

He is just the same delightful enthusiastic boy he always was. He had been doing an infantry spell in the trenches, and had been on patrol, and was bubbling over with his experiences. He is of the sort who only sees the good in people, and all his geese are swans. He ended up by saying, ‘The family is doing quite well. You’ve got the D.S.O., and Uncle Vincent has the M.C., and I’ve got my second pip!’

Young Osmund sounds, indeed, to have possessed many of the splendid qualities that marked out his uncle. Yet the world would not have much longer to enjoy them. At Hervilly Wood, near Roisel, just over a fortnight later, Osmund would be killed.

The young Lieutenant Osmund Stapleton-Bretherton