FEAR MAKES HUMAN beings unrecognisable. Thwarted hopes provoke them into bad, bad decisions.

Thus it was that the Germans kept on fighting long after it made any sense. As a result, catastrophic injury and death needlessly accrued, and scores of towns and villages were razed as their retreat gathered pace.

Rank-and-file German soldiers were not much better or worse than any other soldiers. They got along well with most Tommies when fate threw them together — other than on the battlefield. In the drear phrase, they were only obeying orders, and the drive to fight every step of the retreat can be traced back to Ludendorff and Hindenburg. On the other hand, such dogged resistance would never have happened had not the call for resistance resonated with great swathes of the Imperial Army. That was especially true among officers, and within Prussian regiments — although not, of course, exclusively. Hitler was a corporal, and fought in a Bavarian regiment.

The refusal to confront the implications of defeat had nothing to do with patriotism. It was a cynical consequence of fear and shame by those charged with the leadership of Germany. Nor, although the military sought very hard to do so, can the moral responsibility be laid at the feet of ministers, who came and went rapidly and were quite unused to the power. Since the war had begun, it had reposed in the hands of the military — more with every month which passed — and less and less in the hands of the Kaiser. Now all parties gave themselves over to buck-passing.

What was Germany? In its short history, it had already demonstrated deep fissures and contradictions. Inevitably these were now laid bare. Autumn 1918 was the start of what would prove a long national nightmare which would eventually metamorphasise into the catastrophe of Nazism and another World War. But, during these next days and weeks, it was soldiers and civilians across Europe who would pay the price.

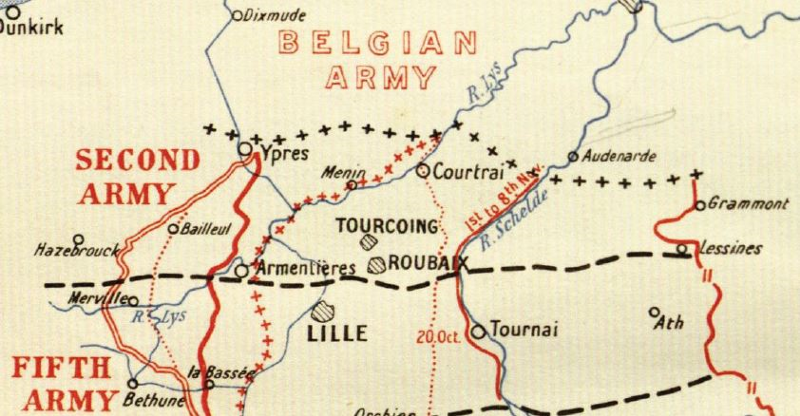

Fighting through Flanders

It was also a week of dramatic progress by the Allies, climaxing in the recapture of key towns and the liberation of the Belgian coast. Following the launch of the great attack in Flanders the previous day, the British took Menin on 16th October and, the next day, entered Douai and captured Lille. That same day, Ostend fell. While Belgian soldiers made a land assault, King Albert of Belgium and Queen Elisabeth arrived by sea in the company of the British Admiral Sir Roger Keyes — one of the huge show-offs of the twentieth century, but a remarkable sailor nonetheless. At the same time, the cavalry was reaching the gates of Bruges after two days of fighting. Here, in sharp contrast to almost everywhere else, the Belgians found its medieval beauties miraculously undamaged.

Douai

By 20th October, with Zeebrugge occupied by a Belgian force, the entire Belgian coast was in the hands of the Allies. Still, however comprehensively the Germans were by now retreating, counter-attack was deeply ingrained into the psyche of many troops, especially of machine-gun crews. On 17th October, the British Fourth Army attacked on a nine-mile front, eventually crossing the river Selle. The cost was ghastly — as Corporal George Parker of the Sherwood Foresters recalled:

We managed, with great loss, to get over some pontoon bridges that the engineers and pioneers had miraculously rigged up overnight, cleared some trenches there, with bayonets and grenades, took more prisoners, mostly boys younger than me. In front of us across a flat area was a ridge, which as we approached erupted with tremendous machine-gun fire. Our officers were killed in getting to that ridge and by the time we reached its shelter all NCOs but myself and another corporal were either dead or wounded.

My team, now only three, and I set up our Lewis gun on the top of the ridge, keeping heads well down. Suddenly lines of grey figures swarmed over towards the ridge, they were putting in a counter-attack! I opened up with my gun, traversing left and right over the plain. I could actually see men falling like ninepins, but still they came on, reinforced by more and more waves of field grey. I thought we had had it.

Parker and the remaining men found themselves surrounded, then wounded, and eventually he had to drag himself away “in between hundreds of our dead”.

Here he met other wounded men, trying to escape:

I met a man from the 5th Sherwoods who had one eye shot out. We were both bleeding like hell, but there wasn’t time to think about it. We crawled along together, coming across an officer, lying in a hole groaning. He had been shot through a lung and had struggled so far before giving up. Poor devil, every time he breathed, blood and foam bubbled from holes in his chest. There was no hope for him, nothing I could do. He asked for water. I still had some in my water bottle and gave him the bottle to keep. He asked me to take his wallet and identity discs. We stopped with him until he died, his last words were to thank us, what for poor chap, I don’t know, we couldn’t do anything for him!

None of this was going to change the inevitable drift of war, and many Germans knew it. Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria wrote imploringly to the Chancellor, Max von Baden, on 18th October:

Crown Prince Rupprecht

Our troops are exhausted and their numbers have dwindled terribly… I do not believe there is any possibility of holding out over December, particularly as the Americans are drawing about 300,000 men monthly from beyond the ocean…

Ludendorff does not realise the whole seriousness of the situation. Whatever happens, we must obtain peace before the enemy breaks through into Germany; if it does, woe on us!

American troops were having a particularly hard time, painfully making their way forward in the Meuse-Argonne. Their target was the capture of the Kriemhilde Line, the last bastion of General Gallwitz’s defence. Following three days and nights of gruesome fighting, Brigadier-General Douglas MacArthur, (another big show-off, but he led from the front), and his men of the 83rd Brigade of the 42nd “Rainbow” Division captured this last great German redoubt on 16th October.

Brigadier-General Douglas MacArthur and his Staff

Pershing’s diary betrays anxiety. Morale and firmness of purpose on some parts of the line may have been wavering. On 15th October, he personally went round the headquarters of the several Divisions and noted later:

At each Headquarters where troops were in line I gave orders that they hold every inch of ground gained. It seems that in many cases troops have taken ground, then, due to their receiving no orders or to their having been subject to machine-gun fire, they have fallen back and the ground had to be taken another day. In certain cases ground has been taken and abandoned four times.

The ferocity of the struggle was a shock to the Americans. Pershing was very sensitive to criticism he felt was coming from the French. One of the soldiers wounded in this action, Private Sam Ross, wrote to his grandmother in New York on 18th October in more philosophical terms:

I have been over here almost a year and do not regret it. The hardships and dangers I have been through have helped me to find myself, to find out my good and bad, mostly bad points.

The casualties on both sides were dreadful: Gallwitz’s Army Group lost 80,000 killed, wounded or taken prisoner, but the Americans suffered 117,000 casualties during the Meuse-Argonne offensive — almost 40 per cent of their total losses for the war.

American casualties in the Argonne

The cost of war was also being understood in more explicitly material terms. Retreating Germans soldiers inspired hatred and outrage for the pillage and destruction often wrought upon civilians. This was a matter upon which the fourteen-year-old schoolboy Yves Congar, later a Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church, boiled with indignation in the pages of his diary:

The Boches’ behaviour in France is scandalous. The loot they are taking back to Germany is unbelievable: they’ll have enough to refurbish every one of their towns! But one day soon it will be our turn: we will go there and we will steal, burn and ransack!

A more temperate analysis came on 17th October from Lieutenant John Nettleton of the 8th Division. He was one of the first to enter Douai:

As far as the buildings were concerned the town was more or less intact. But inside the buildings everything of value had been removed and everything else wantonly smashed and destroyed. Not only things that might have been of use to us, but everything: mirrors, furniture, pictures, crockery, even the organ in the cathedral — all smashed to atoms. Mattresses were split open and the stuffing scattered; even children’s toys were broken up in a senseless orgy of destruction. I saw a French gendarme weeping openly as he looked at the wreck of his home and held in his hands the remains of a broken doll.

The damage done by modern warfare is appalling enough — there is absolutely no point in going to so much trouble to make it worse.

Even Lieutenant Colonel Feilding, an abiding source of sanity and circumspection, seems to have been rattled. On 15th October, he told his wife:

For two days, until we reached the old German front line of the summer this year, we had marched over country and through towns as big as Portsmouth or Southampton, not one house of which has escaped the destroying hand of the enemy. This is literally and emphatically true. Not even the most humble cottage has been overlooked, so ‘thoroughly’ has the work been accomplished.

During the latter part of the march we passed a woman or two, here and there, who had just returned following up the enemy’s withdrawal, to inspect the damage done to their homes. It was very harrowing to watch them. Some of the very young seemed cheery enough, but the others wore sad faces as they searched the ruins with their handkerchiefs to their eyes, picking out bits of broken crockery or any kind of rubbish, and collecting, with the utmost care, old, ragged, shell-torn or half-burnt clothing — stuff, one would think, fit only for the incinerator.

It is tragic, and, if the people who were responsible for these cruel outrages are to be let off, it is all wrong…

A description from Second Lieutenant Frank Warren of the King’s Royal Rifles, in a letter of 15th October, alludes to the social as well as physical repercussions of occupation:

We are passing through French villages now released from the German yoke. It is a pleasure to find many villages little damaged, as compared to the wilderness created by the Hun in his spring retreat of 1917… all are delighted to be ‘libres’, and look forward now to white bread, sugar and ‘beaucoup de viande’. I am told that one or two girls left the village arm in arm with the German soldiers; even if it is true, it is not very surprising, seeing that the same troops have been in occupation for about four years…

Belgian women celebrating the liberation of Ostend

The costs and casualties of war were way too various for any single calculus. While the liberated territories in the West tried in bewilderment to resurrect themselves, the Civil War in Russia still elided confusingly with what had once been the Eastern Front. On 18th October, the British repelled a far superior Bolshevik force at Seletsko, 160 miles up the Dvina river from Archangel, at much the same moment as a Czecho-Slovak force was pushed back by the Bolsheviks in Eastern Russia. Allied strategy in the East, however, was virtually impenetrable.

Superficially, the Southern Front offered a greater clarity of purpose: on 16th October, it was announced that Greece was cleared of any Bulgarian forces and later, that Bulgaria was now free of German troops — another place in which their pillaging had been notorious. Italian units had begun preparations for an attack in their mountains and began fighting on the Asiago and Grappa Fronts.

Yet what on earth could the future hold in these regions? The implosion of the Romanovs, and the imminent collapse of the Habsburg and Ottoman empires presaged mind-boggling demographic challenges and ethnic struggles. The immensity of Britain and France’s struggle against Germany had always swallowed up the great bulk of both nations’ material and moral resources, but the advent of probable peace suggested a day of reckoning in south-eastern Europe and the Middle East could not be delayed much longer. On 15th October, in a sign of the higher profile which the Allies had now assumed, British cavalry entered Homs in Syria.

Homs, 1918

The Yugoslav desire for independence received some welcome acknowledgement from Emperor Karl of Austria-Hungary on 16th October when he issued a Manifesto granting autonomy to “Yugo-Slavs”, as they were then known, and there was a Proclamation in Prague of a Czech Republic. This was all music to the ears of President Wilson, a great apostle of national self-determination, although he warned the Austro-Hungarians that these concessions would be insufficient to merit an armistice. He was an even more strident fan of an independent Poland and the British government, perhaps in an effort to win some easy credit, recognised the Polish army as autonomous on 17th October.

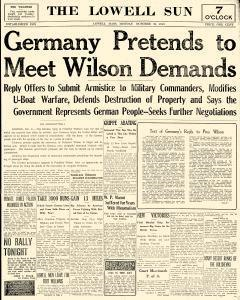

Getting the Germans to bow to the inevitable was always going to be harder. However, after much soul-searching, the new German Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, told Wilson on 20th October that the country was ready to abandon its policy of unrestricted submarine warfare — a moment of truth, if ever there was one. Submarine warfare had threatened to bring the Allies to their knees only months earlier.

Prince Max of Baden (in the peaked cap) with his Vice-Chancellor, Von Payer (on his right), leaving the Reichstag, October 1918

Ludendorff was disgusted:

This concession to Wilson was the heaviest blow to the Army and especially to the Navy. The injury to the moral[e] of the fleet must have been immeasurable. The Cabinet has thrown up the sponge.

A cooler head than his might have argued that the German cabinet was simply trying to square up to the truth of things. But the awful reality of its situation still failed to penetrate. Hindenburg and Ludendorff suddenly reverted to optimism, insisting that the rush for peace negotiations was purely a fiction of the politicians, and that military realities weren’t so bad.

But it wasn’t — and they were. In the end, Prince Max made the submarine question a condition of his staying in office, and the military feared his departure (and their own exposure) even more than they despised the show of weakness.

Suspicion of the Germans’ motives in the first overtures for peace ran high

The Kaiser, way out of his depth, oscillated between hope and despair, and pondered his uncertain future. Warned of the rumblings of revolution and of demands for his abdication, he uneasily responded: “A successor of Frederick the Great does not abdicate.”

Not that that changed anything. His words, much like his silly moustache, tended to command attention without making the least difference.

In London, there was a special meeting of the war cabinet to which Haig was summoned. In his diary, he noted down his words to his old nemesis, the prime minister:

The British Army has done most of the fighting latterly, and everyone wants to have done with the war, provided we get what we want. I therefore advise that we only ask in the armistice for what we intend to hold, and that we set our faces against the French entering Germany to pay off old scores.

In my opinion, the British Army would not fight keenly for what is not really its own affair.

Haig reviews Canadian troops on the Hindenburg Line, August 1918

However good he was as a soldier, the minute Haig stepped outside his profession, he seems in some respects to have been acutely limited. The hints of blimpishness — above all, his mistrust of the French — could have come straight out of the mouth of an Edwardian public schoolboy.

On the other hand, the words he gave offered an authentic flavour of the times: the nation in general, and the army in particular, was utterly spent.

Haig added:

Balfour… spoke about deserting the Poles and the people of Eastern Europe, but the PM gave the opinion that we cannot expect the British to go on sacrificing their lives for the Poles.

The Poles were a very sore point. They had been swallowed up by Imperial Russia in the eighteenth century and were now baying for national independence. President Wilson, with what sometimes appeared a blithe indifference to the awesome ethnic and strategic complexities this would necessitate, set about making that happen. From where he was sitting, a new Poland could be easily enough fashioned out of Eastern Prussia and some of the western districts in Russia. If Wilson had simply been some harmless old eccentric, such extravagant ideas would hardly have mattered. However, he was the leader of the free world, and so everyone else was forced to sit up and listen.

Troops of the Polish Legion, 1918

The prospect of becoming entangled in a protracted and murderous war in the East simply in order to gratify him was not one upon which the British cabinet gazed with benevolence. Nor did it appreciate his habit of firing off communications to Berlin without showing them to the Allies first. But this wasn’t, as they knew, a moment to fall out with the United States. The war cabinet restrained its indignation and very politely cabled Washington requesting the President to consult them before again replying unilaterally to Germany.

To agree terms with Germany now — or to go for broke? That was the question. Two decades later, many rued the lost opportunities of these weeks, and even in October 1918, the dilemma was one well understood by many. Sister Edith Appleton in Le Tréport reflected on 18th October:

…I hope we shall not give the Germans peace yet, for the one reason that the men, one and all, are fiercely against it and it is they who bear the brunt. If they feel they can stand a little more of it, why should they be held back?

They feel they have not yet hit back hard enough for the dirty, mean, brutal tricks played by the very dishonourable enemy. Given another few months they may make a far more satisfactory job of it…

In a letter home written three days earlier, the army chaplain, Reverand Julian Bickersteth, had been thinking something rather similar:

Germany is done but wants to crawl out before all is lost. And this, I think, we cannot afford to let her do, or the war will start up again in ten years time.

This showed an uncomfortable prescience. The hardest yards of a prolonged struggle often prove to be the last ones.

Julian Bickersteth

These were now made harder still by the onset of virulent influenza — the so-called Spanish influenza. Having gone into abeyance for some months, it now returned — virulent and pitiless. The relentless diarist, Thomas Livingstone, recorded on 15th October: “310 deaths in Glasgow last week from influenza.”

It was no accident, of course, that it struck a world which was cold and hungry as well as exhausted. Two days later, Livingstone noted laconically: “Father here at tea time. Says he came here to get warm as they have no coal…”

British soldiers on leave, 1918

Flu now featured regularly in the daily list of deaths of British and Dominion military and medical personnel. This week’s total of deaths was 8,427. Captain Charles Carrington recorded on 20th October that its victims included young conscripts being trained, supposedly, to join the war effort:

We’ve had 17 or 18 deaths in the Battalion and 200 or 300 cases, nearly all raw and unhardened recruits from the West of England. We, who’ve done winters in the trenches, feel pretty safe against little things like this. (I’m touching wood.)

In Europe, 40,000 Americans had been hospitalised during the month of September. On 15th September, writing from Neufchateau, Dr Harvey Cushing recorded the experience of Bagley, a fellow doctor:

The usual story. This time Transport 56 — i.e., the Olympic. He was ship Medical Officer. There had been no grippe in the States (?), but nine cases developed on the boat, with one death from pneumonia. They were held in Southampton Harbour 24 hours before disembarking, and 384 cases developed during this brief time — very severe — temperatures of 105° frequent in men at the very outset. People standing guard would fall in their tracks. They were sent to a rest camp near Southampton and in a week 1900 cases developed, with several hundred pneumonias and 119 deaths before he left. Of the 342 nurses who were left on shipboard after the troops disembarked, 134 developed influenza.

Cushing had many reasons to grieve. That same day, he recorded a piercing tale of unsung heroism:

…They were bringing up coast-guard guns and were passing through a French village – a row of caterpillar tractors towing the heavy pieces, also on their caterpillars… On the side of the road were some doughboys, dealing out bits of chocolate to an eager group of French children. Suddenly a little girl on the opposite side of the road caught sight of them and, oblivious of the traffic, darted across the road to get her share…

Quick as a flash the gunner swung under the long barrel of which he was astride, caught the child while almost in the air, and threw her back into the road, but before he could recover himself the caterpillar of the gun carriage went over his head.

There are no words for this sorrow — there could not possibly be. In these terrible days, God seemed to have become exacting beyond reason, or just cruel.

But there were good moments for some — there always were. Julian Bickersteth’s brother, Burgon, who had just been in horrendous fighting and won a bar to his MC, was unexpectedly given leave. So off he went to Paris — his first proper jaunt since the outbreak of the war — and did himself proud. So he should have done.

21 October Voici les changements de la guerre! Two of us arrived yesterday afternoon, in an express train just as fast as in peace time, and we actually crossed the country where we had been fighting, or rather billeted, just before the fight, and saw the woods where we had fought — further on passed a field where I had slept in the open.

We could not get in the Ritz and so came here [Hotel Mirabeau]. Of course everything is in the height of luxury. Last night we dined in the Cafe de Paris, and went to the Folies Bergère.

Civilian and soldier; liberation of Lille, October, 1918